Dr. Melanie King (Loughborough University)

The European Union’s (EU) new battery regulations (Regulation 2023/1542 ), introduces many new legislative measures, including specific requirements for battery passports and smart labelling. It marks a significant shift towards enhancing sustainability and transparency within the battery value chain.

These battery regulations are pivotal in advancing the EU’s Circular Economy Action Plan. As the UK navigates its post-Brexit landscape, aligning with these regulations is crucial for maintaining trade relations and environmental standards. Recent InterAct funded research provides a comprehensive analysis of the UK’s readiness to adapt to these regulations, offering insights that highlight both opportunities and the challenges ahead.

New regulatory requirements

Under the new rules, there will be enhanced information and ICT system requirements for entities introducing batteries and battery powered products to the market. This applies to any economic operator involved in making batteries available in the EU, whether as separate components like cells, modules and packs, or as part of larger products. It also includes those who change a battery’s intended use or are involved in refurbishing or remanufacturing.

A key feature of the regulation is the mandatory inclusion of a QR Code on all batteries, facilitating the use of ‘smart label’ and ‘battery passport’ functionalities, varying by battery type. While specific operators are obligated to provide this information, in practice, a broader network of stakeholders will likely contribute, creating an integrated, multi-stakeholder ‘battery information ecosystem’. This ecosystem will span the entire value chain and lifecycle of battery products, supporting both passport and smart label functions with information from a diverse array of operators.

UK readiness

Recent research conducted by Loughborough University (supported by the Made Smarter Innovation Challenge and funded via the Economic and Social Science Research Counil (ESRC) led InterAct Network) offers an extensive overview of the UK’s readiness for the impending regulations, specifically Battery Passports and Smart Labelling requirements.

The analysis includes results from a nationwide survey, completed by 80 organisations, including 21 large, 28 medium-sized, 23 small enterprises, and eight micro-businesses, also representing a wide spectrum of products and activities across the battery value chain/system.

The findings from the survey were discussed in a roundtable discussion and follow-up interviews, available here, which offer a multi-dimensional perspective on the readiness and concerns of the UK battery sector. This breadth of participation underscores the comprehensiveness of the findings, capturing a wide array of viewpoints and insights from a variety of actors along the value-chain from beginning of life to end of life.

Awareness and attitudes towards regulation

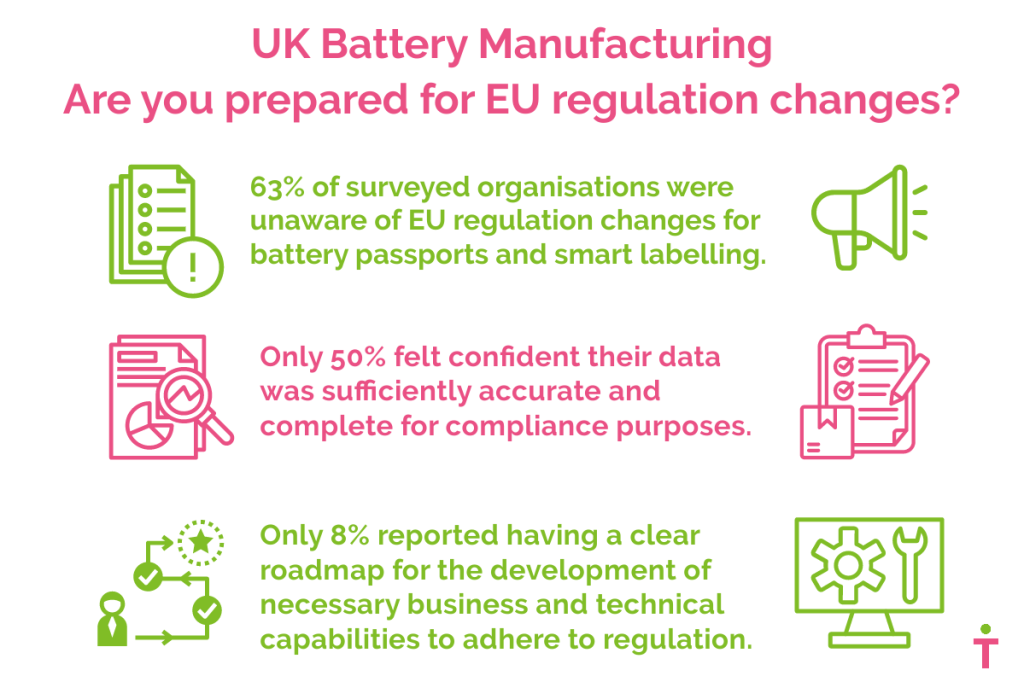

The survey revealed that 63% of organisations were unaware of the new regulations, with this figure rising to 73% among UK-based suppliers to the EU. This lack of awareness is concerning, as it indicates a potential gap in readiness for compliance.

The industrial context of these regulations is complex. While there is optimism about the potential for more sustainable and circular business practices, there are also concerns about the administrative, technical and financial burdens the Battery Passport and Smart Labelling requirement might impose. The majority view these requirements as a significant challenge, with only a minority seeing any substantial benefits.

Information readiness: a critical gap

A significant challenge identified in the survey is information readiness. Many businesses reported inadequate access to crucial data on battery materials and supply chain details. This includes information on recycled material content, hazardous substances and critical raw materials, as well as supply chain transparency for components like battery separators and cell casings.

Only about half of the respondents felt confident in the accuracy and completeness of their records, highlighting a pressing need for improved information sharing and data management systems.

ICT challenges and opportunities

The survey underscored the significant challenges in ICT, data, and workflow requirements for compliance. The responsibility for the Battery Passport primarily lies with the manufacturer, who is required to create and maintain these records for each battery throughout the battery’s lifecycle.

In some cases, other economic operators also have roles to play in maintaining or updating certain information, yet many organisations lack the necessary systems and expertise to collect, create, share and report the required data. However, this also presents an opportunity for innovation in the sector, with the potential for new technologies and systems to streamline these processes.

Implications for UK battery producers and UK policy

More needs to be done to raise awareness and demystify the compliance obligations of UK battery manufacturers and producers. It was felt that the new regulations would dominate the focus of day-to-day business activities for several years.

Other issues raised – such as fragmented industry practices, lack of clear guidelines, and the complexity of supply chains – would benefit from clear policy directions, enhanced data management systems, and increased international and value-chain collaboration, which were seen as critical to overcoming these challenges.

The regulation necessitates a collaborative effort from manufacturers, producers, importers, and distributors of all battery types and is essential for implementing substantial changes in areas such as labelling, end-of-life management, and supply chain due diligence. Additionally, there is a need for establishing incentives that will enable increased collaboration between beginning-of-life and end-of-life operators.