Overview

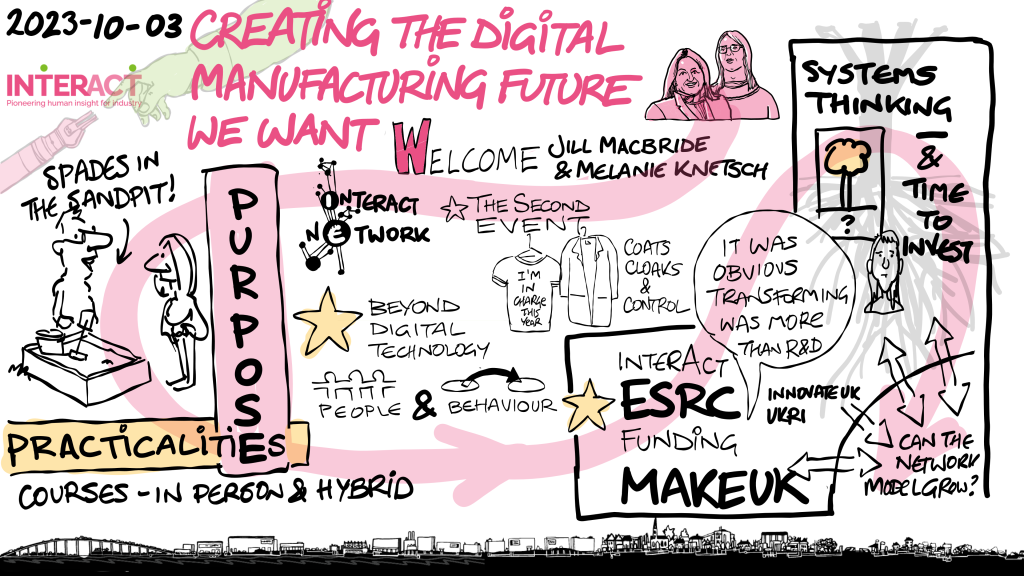

As we embark on the next stage of our industrial evolution, digitalisation will shape the future of our economy, manufacturing ecosystem, and workplace. Digital technologies can enable us to create the future we want and move beyond consumption driven economic growth.

Our challenge is to create a digital manufacturing future that meets our net-zero ambitions, whilst being resilient and productive. Thus, ensuring that everyone has the things that they need, at a price that they can afford, without damaging the environment or society.

To create the digital manufacturing future we want, we first need to know how that can be achieved, we need to explore the possible and work together to realise these goals. In order to combine our expertise from the broadest range of perspectives around this common goal, we need to InterAct.

How did the InterAct conference benefit attendees?

- Gaining actionable human insights into the future manufacturing environment.

- Networking and building relationships with cross-sector experts interested in creating a positive, forward-thinking vision for UK industry.

- Building narrative development skills to enhance the reach of messaging in the digital environment.

- The opportunity to take part in a collaborative workshop on the theme ‘How do we create the digital manufacturing futures we want to see, together’.

- Engagement with a panel of highly regarded speakers from the world of manufacturing, policy, and academia during an interactive Q&A session.

Speakers

We were delighted to welcome a roster of world-leading speakers, who shared unique insights and perspectives on their areas of expertise in relation to the theme of ‘Creating the digital manufacturing future we want’.

Our speakers were drawn from a wide range of backgrounds across industry, policy, think-tanks, and academia. Together they represent a diverse collection of voices that we want to draw into the wider conversation about what it will take to build a future that delivers for everyone.

Please complete the captcha to download the file.

Download “InterAct Conference sketches” InterAct-Conference-Sketches.pdf – Downloaded 2388 times – 6.17 MB

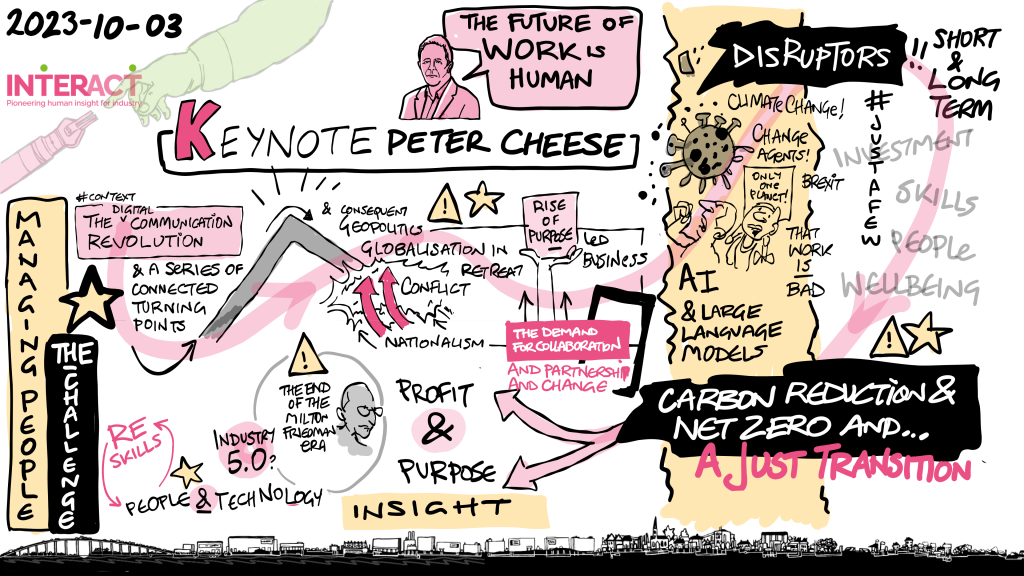

Peter Cheese

Keynote Speaker

Chief Executive – Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development (CIPD)

Peter is the CEO of the CIPD, the professional body for HR and People Development. Since January 2019, he has been co-chair of The Flexible Working Task Force, a partnership across government departments, business groups, trade unions and charities, to increase the uptake of flexible working. He is also Chair of Engage for Success and the What Works Centre for Wellbeing.

Peter writes and speaks widely on the development of HR, the future of work, and the key issues of leadership, culture and organisation, people and skills. In 2021, his second book ‘The New World of Work’ was published, exploring the many factors shaping work, workplaces, workforces and our working lives, and the principles around which we can build a future that is good for people, for business and for societies.

Prior to joining the CIPD in 2012 Peter was Chair of the Institute of Leadership and Management, an Executive Fellow at London Business School, and held a number of Board level roles. He had a long career in consulting at Accenture working with organisations around the world, and in his last seven years there was Global Managing Director for the firm’s human capital and organisation consulting practice.

He is a Fellow of the CIPD, a Fellow of AHRI (the Australian HR Institute), the Royal Society of Arts, and the Academy of Social Sciences. He’s also a Companion of the Institute of Leadership and Management, the Chartered Management Institute, and the British Academy of Management. He holds honorary doctorates from Bath University, Kingston University and Birmingham City University, and is a Visiting Professor at Aston University.

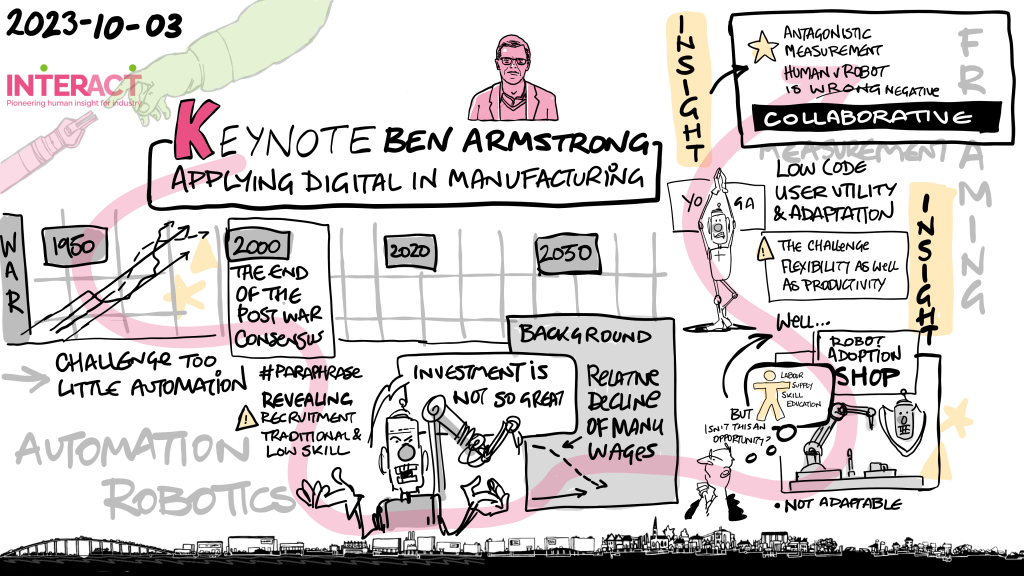

Ben Armstrong

Keynote Speaker

Executive Director – Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) – Industrial Performance Center

Ben Armstrong is the executive director and a research scientist at MIT’s Industrial Performance Center, where he co-leads the Work of the Future initiative. His research and teaching examine how workers, firms, and regions adapt to technological change. His current projects include a working group on generative AI and its impact on work, as well as a book on American manufacturing competitiveness. He received his PhD from MIT and formerly worked at Google Inc.

David Rea

Speaker – Future of the Economy

Chief Economist – JLL

David is Chief Economist EMEA at JLL, one of the world’s largest commercial real estate services companies. At JLL, David advises the firm’s leadership and its clients on how the economy is evolving and the impact it will have on real estate. Prior to JLL, David spent six years as Chief Economist at Jaguar Land Rover and also led the company’s work to prepare for Brexit. He has previously held other economist positions at Capital Economics, RBS, and the Bank of Sierra Leone.

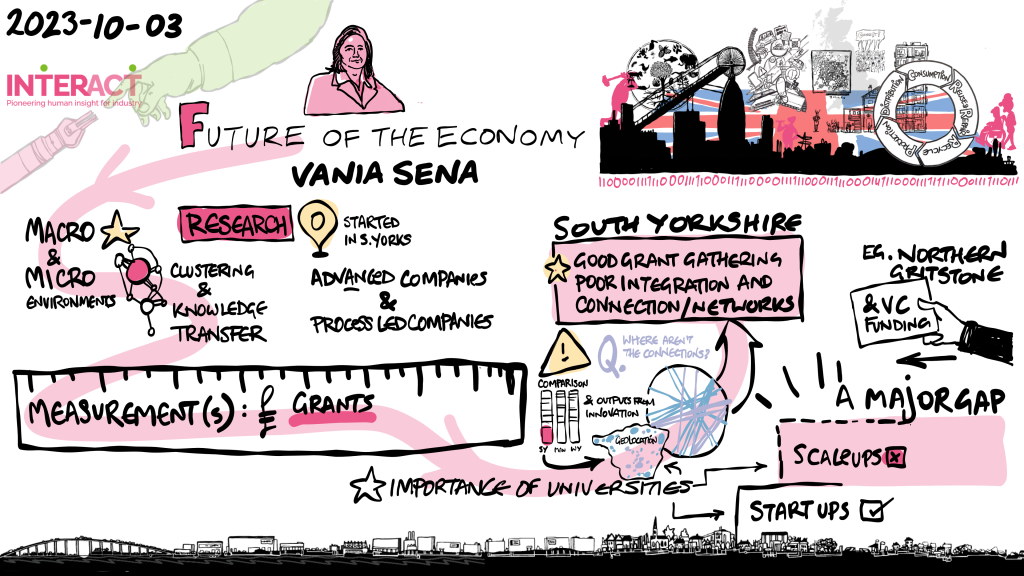

Professor Vania Sena

Speaker – Future of the Economy

InterAct Network – Future of the Economy: Principal Investigator

Chair in Entrepreneurship and Enterprise – University of Sheffield

Professor Sena’s first degree was awarded with laude by the University of Naples, Federico II, Naples, Italy; her postgraduate studies in Economics were carried out at the University of York, UK, where she was awarded both the MSc and the DPhil in Economics.

Her research focuses mainly on productivity growth, both at the micro and macro level with an emphasis on innovation, human capital and intellectual property. Her most recent research looks at the relationship among innovation activities,trade secrets and total factor productivity. She is a member of the Operational Society General Council and Board. She has been a visiting fellow at Harvard University, MA and at Rutgers University, NJ.

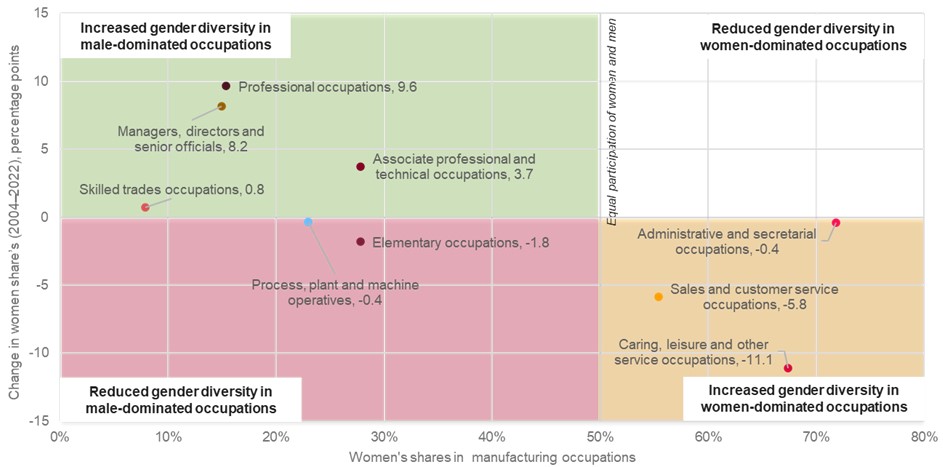

Vania is leading the InterAct workstream ‘The Future of the Economy’, which is examining the impact that the uptake of industrial digital technology in manufacturing will have on the wider economy and the implications of of this.

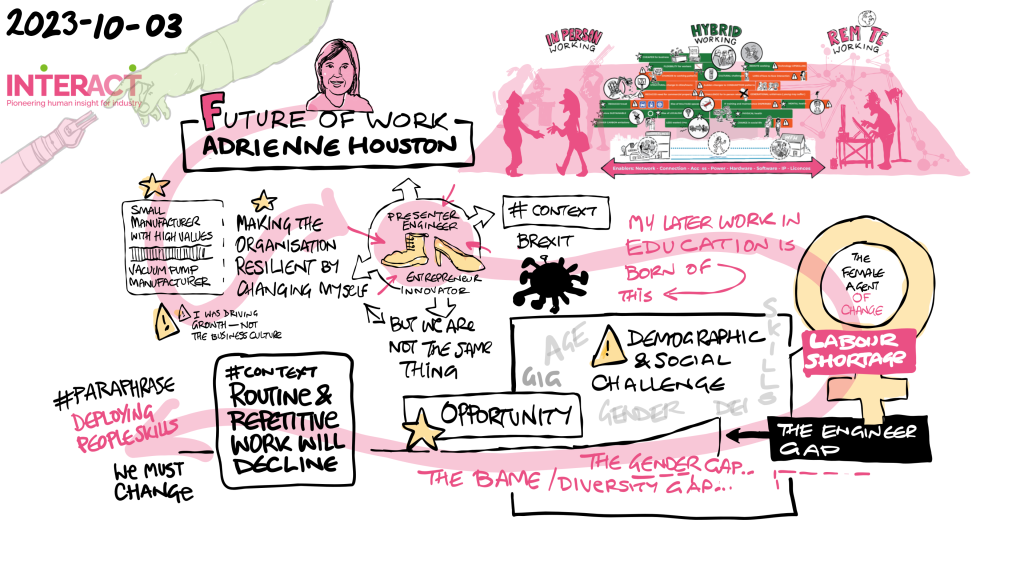

Dr. Adrienne Houston

Speaker – Future of Work

Company Director – Eurovacuum

Dr Adrienne Houston is Company Director at Eurovacuum Products Ltd. She is a Mechanical Engineering specialising in high vacuum and low pressure compressor systems and vacuum evaporator for the biogas, chemical and pharmaceutical industries.

To complement her professional work, Adrienne is a keen promoter and champion of women in engineering, diversity and inclusion. In 2019 she was appointed by the Royal Academy of Engineering for the role of Diversity and Inclusion Visiting Professor at the University of Birmingham. She is a board member at the Research, Information and Knowledge committee at the Engineering Professors Council and Honorary Visiting Design Professor at the School of Engineering, University of Leicester.

Professor Jillian MacBryde

Speaker – Future of Work

InterAct Network Co-director

Professor of Innovation and Operations Management – University of Strathclyde

Jill MacBryde is Professor of Innovation and Operations Management at Strathclyde University where she is also Director of the Hunter Centre for Entrepreneurship. Jill is Co-Director of the ESRC Made Smarter Network Plus, InterAct network, which aims to bring insights from the social sciences to support the innovation and diffusion of digital technologies that will result in a stronger, more resilient, manufacturing base.

The theme throughout Jill’s work is operations management in changing environments and her current research projects include productivity in manufacturing, the impact of Covid on UK manufacturing, and the future of manufacturing work. Jill also works with policy makers and the public sector. She is currently a member of the Innovate UK/ESRC Innovation Caucus and a member of the Innovate UK Future Flight Advisory Board.

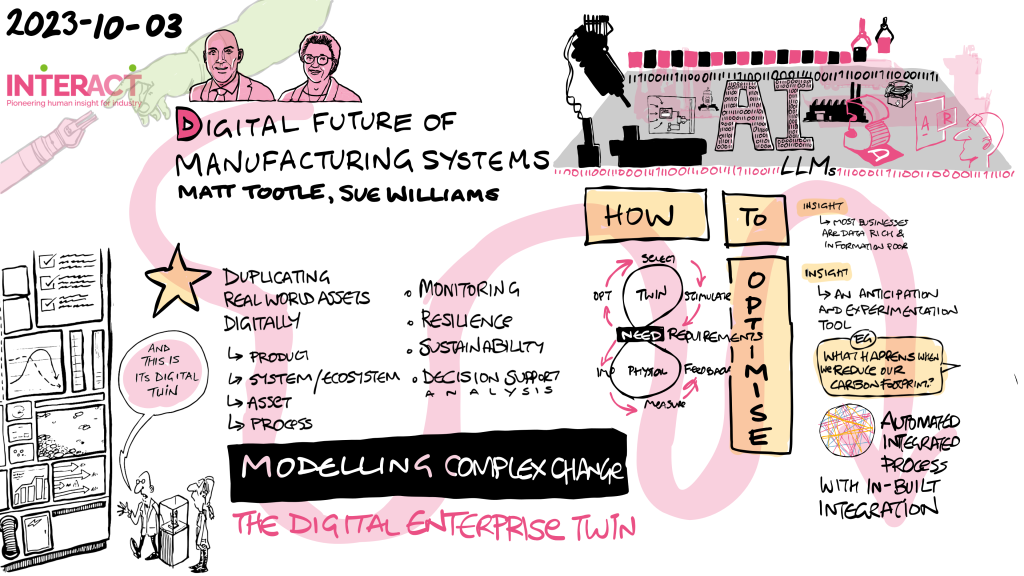

Matt Tootle

Speaker – Future of Digital Manufacturing Ecosystems

Senior Business Analyst – Aerogility

Matt is an energetic and passionate leader who joined Aerogility with over 16 years’ experience in defence aerospace, primarily within support engineering and manufacturing. Matt’s specialisms include capturing and shaping complex customer requirements, designing and developing deliverable solutions and translating technical problems to non-technical individuals. Matt has extensive experience working with international customers and colleagues to deliver value to their operations. Matt’s current role sees him working across a variety of sectors to deliver innovative, model-based AI solutions to enable customers to better operate, sustain and optimise platforms, services and infrastructure.

Sue Williams

Speaker – Future of Digital Manufacturing Ecosystems

Managing Director – Hexagon Consultants

Sue Williams is a strategic and focused Supply Chain Director with over 25 years’ experience in multiple industries including automotive, aerospace, defence and FMEG as well as aftermarket and aftercare support. Sue’s specialisms include supply chain design and modelling, inventory planning, demand management, S&OP and supply planning. Sue has worked with organisations such as Jaguar Land Rover, Dyson, GKN and Meggitt among others, to deliver sustainable, high value change to their supply chains. Sue was also the Head of Supply Chain for the Vaccine Taskforce, responsible for supply chain risk and resilience and the inbound modelling and planning for the vaccine supply.

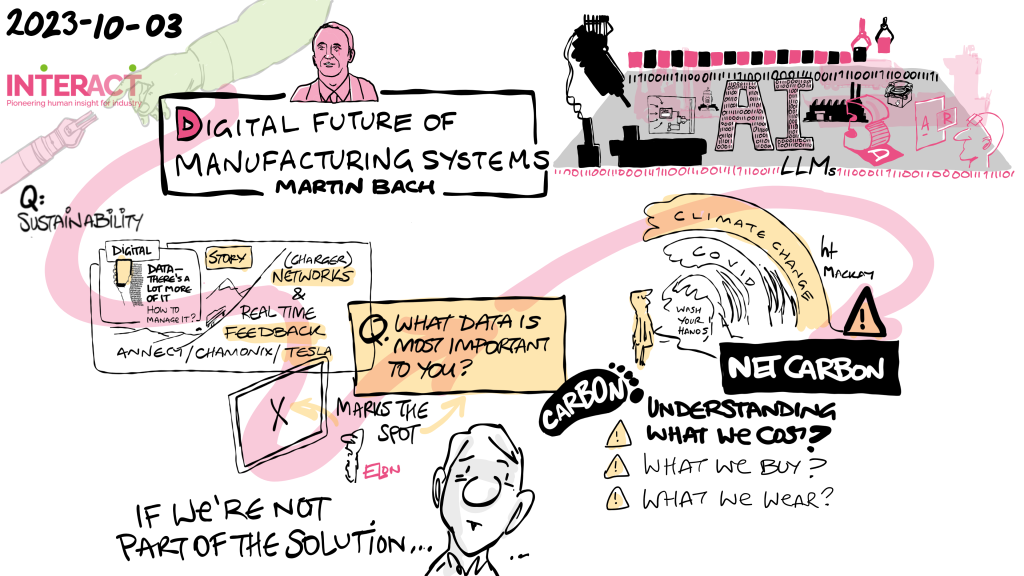

Martin Bach

Speaker – Future of Digital Manufacturing Ecosystems

Martin Bach’s background is in process engineering and manufacturing management. He has extensive business management experience in the UK, Europe and the US, running a wide range of businesses in the automotive and industrial sectors. Most recently he was Managing Director of Cooksongold, the UK’s leading supplier of jewellery making materials and products.

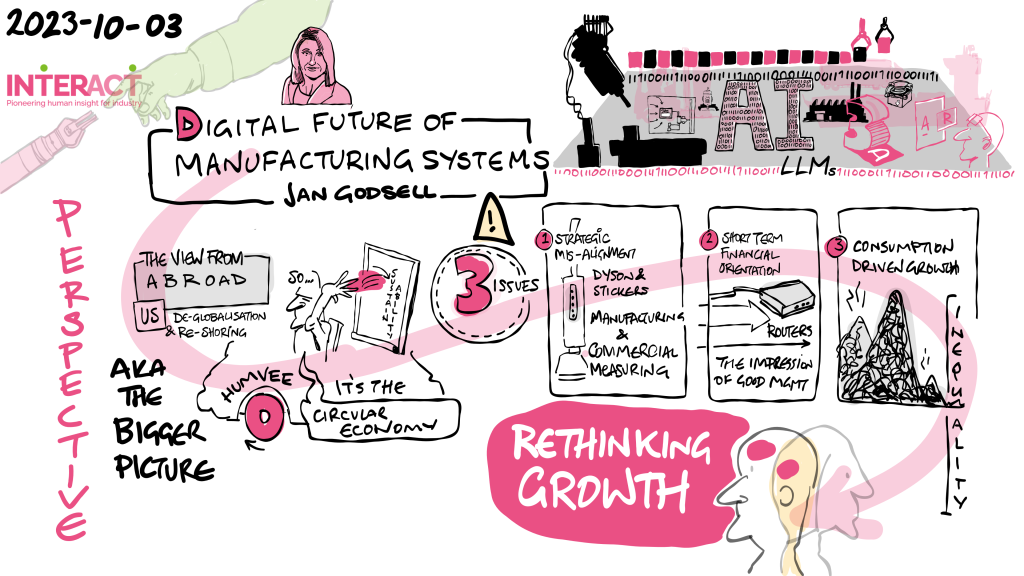

Professor Janet Godsell

Speaker – Future of Digital Manufacturing Ecosystems

InterAct Network Co-director

Dean of Loughborough Business School – Loughborough University

Jan Godsell is Dean of Loughborough Business School and Professor of Operations and Supply Chain Strategy at Loughborough University. Her work focuses on the pursuit of more responsible consumption and production through the alignment of product, marketing, and supply chain strategy with consumer needs. Jan’s work focuses on the design of end-to-end supply chains to enable, responsibility, sustainability, resilience and productivity.

Jan is the workstream lead for ‘The Future of Digital Manufacturing Ecosystems’. This will examine how to develop more sustainable manufacturing business models, supply chains, and the role of innovative digital technologies (IDTs) in facilitating this shift.

Ved Sen

Keynote speaker

Head of Business Innovation – Tata Consultancy Services (TCS) UK

Ved is passionate about the impact of technology on business, culture, and society. He enjoys speaking and writing about technology and the future. He writes a weekly innovation newsletter, and is a regular speaker at industry forums. He has been a guest lecturer at the HSE Ireland Masters in Digital Healthcare Programme in Dublin for the past 3 years, and a regular speaker on AI and future systems.

Ved works as the Head of Business Innovation for Tata Consultancy Services UK. His primary focus is to help drive future thinking conversations with clients in solving tomorrow’s problems. He has been working with and advising senior clients across retail, travel, education, healthcare, financial services, public sector, and other businesses. Ved runs an innovation team in London and is leading the design and set up of Pace Port London. Currently his work spans areas such as reinventing social care for the elderly, connected homes and environments, and urban mobility, Generative AI, and more. Over the past 20+ years, Ved has been working on emerging technologies, and their adoption into organisations. An avid writer and regular speaker, Ved’s book “Doing Digital” was released in January 2023, and he writes a regular innovation newsletter.

Fhaheen Khan

Panellist

Senior Economist – Make UK

Fhaheen Khan is a Senior Economist at Make UK, the manufactures organisation. His role primarily focusses on monitoring and evaluating the economic performance of manufacturers, which is published in a quarterly outlook report. In addition, Fhaheen’s role covers a myriad of topics relevant to manufacturing to advise Government bodies to develop policy with a focus on tax, investment and the business environment and is a regular commentator on public statistics.

Ben Farmer

Panellist

Deputy Director – Made Smarter Innovation Challenge

Ben is the Deputy Director of the Innovate UK-led £300 million Made Smarter Innovation Challenge; a collaboration between UK government and industry designed to support the development and novel application of industrial digital technologies.

Prior to this, Ben held positions at HiETA Technologies, Airbus Group, University of Bath and Cobham. He is also founder of Added Lightness, a technology strategy consulting business, and Atherton Bikes, which brings together multiple-world champion and world cup winning athletes with the latest composite and additive manufacturing technologies.

Ben holds a degree in Materials Science and Engineering and an MBA from the University of Bath, a PhD in Materials Science and Metallurgy from the University of Cambridge and is a Chartered Engineer.