Ask anyone involved in supply chain management or logistics about the last five years and most will agree they have been tough. Brexit, Covid and the war in Ukraine have caused uncertainty on both the demand and supply side.

Such geopolitical uncertainty raises complex questions for supply chain managers, such as whether supply chains could be better prepared for shocks.

Professor Jan Godsell is the Co-director of InterAct and Dean of Loughborough Business School and Professor of Operations and Supply Chain Strategy. After a career in manufacturing and supply chains, including spells at ICI and Dyson, she moved into academia covering all aspects of supply chains. According to Jan, a common cause of supply chain breakdown is just a lack of joined up thinking between marketing and supply chain strategy.

“It doesn’t matter whether you know why a demand pattern has been caused,” she explains. “If there’s a peak in demand, there’s a peak. The data should show that you get seasonal peaks, and you can react. We know we’re going to get shocks. We won’t know the cause, but we can have a degree of preparedness knowing there will be shocks at some stage.”

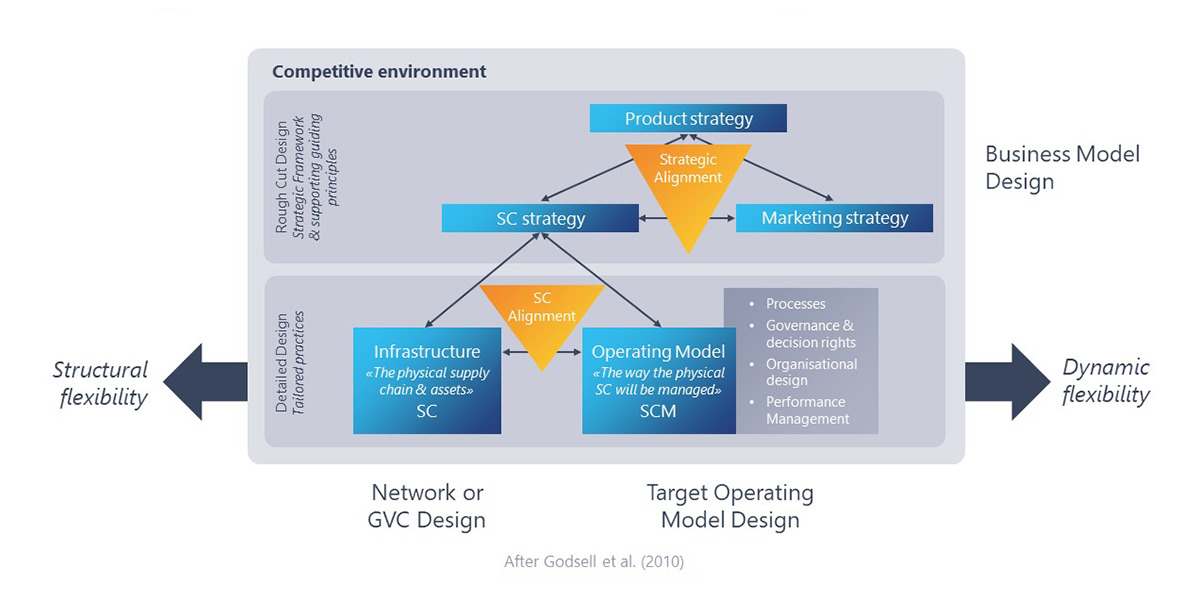

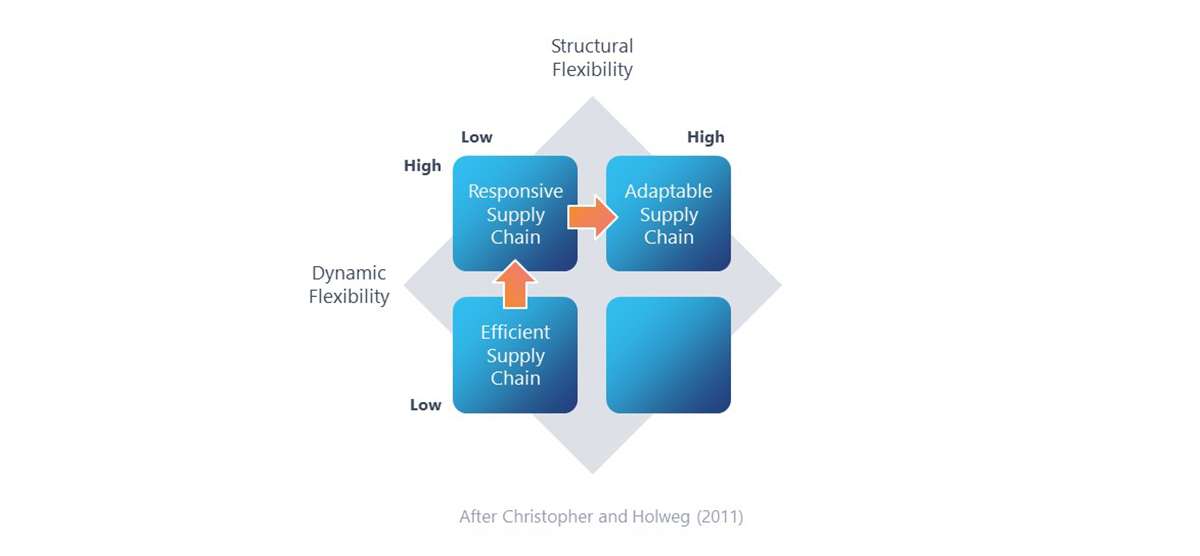

Dynamic versus structural flexibility

Dynamic flexibility is possible within the current network design, while the other, structural flexibility, demands a rewiring of relationships between suppliers.

She says the first type should be enough to cope with everyday swings in demand and supply. “If things stay within standard parameters, the network needs the right buffers to deal with that variability. It is a matter of analysing and assessing how unpredictable demand might be and using maths to work out required buffers and what inventory to keep.”

Jan says exceptional events in recent years have seen both sorts of flexibility at play.

“Brexit forced the UK to be fairly well buffered, so when Covid hit it meant we had a lot of inventory for the things we normally need. What also happened was unexpected demand for things we don’t normally require, such as Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) and ventilators.

“That required structural flexibility, creating new networks to produce things at a volume not seen before. With Covid-19, it wasn’t just the UK requiring flexibility, it was the world. We had to repurpose assets in the global network to provide them. And we did a decent job, globally.”

Jan adds that structural weaknesses highlighted by recent events have been partly created by decisions taken over many years, in particular making supply chain decisions based on short-term financials and procurement rather than long-term planning.

Finance runs the supply chain game

Holding buffers or inventory in a supply chain can be expensive, and it’s often not clear who should bear that cost. This, says Jan, is partly why supply chains have not been as resilient as they could be.

“We’ve had a financially orientated view of supply chains, focused on a return on capital employed (ROCE) that enables payback as quickly as possible. That means when building a factory, we don’t factor in spare capacity. And if spare capacity means inventory, we try to maximise return and minimise inventory.”

For Jan this goes back to how we value organisations, and the role finance plays in corporate strategy. And we haven’t learned much from earlier shocks.

She points out that financially driven supply chains had an impact in the recession of the late 2000s. A lot of firms had sent manufacturing and other parts of their supply chains offshore, often to low-cost environments. But they had forgotten to factor in the cost of logistics, which became a problem when the oil price peaked.

“Suddenly, the price of logistics was higher than the price of production. That reminded people to take a ‘total landed cost’ perspective [when deciding on location],” she explains. “People were lazily using manufacturing cost as a proxy for total landed cost. Worse still, they’d started to use labour cost as a proxy for manufacturing cost.”

While current trends such as “nearshoring” and “reshoring” are ways to de-risk supply chains, Jan suggests if cost must be the key factor in a decision, total landed cost is the metric to use. But when deciding where to place operations, she suggests not letting procurement be the drivers. Instead, she says, long-term planning and collaboration across the supply chain will be more effective at delivering efficient, resilient supply chains.

Let the SCOR guide you

Prof Godsell highlights the Supply Chain Council’s Supply Chain Operations Reference model (SCOR). SCOR consists of five core processes:

- Planning

- Procurement

- Manufacturing

- Logistics

- The returns process

Planning is the primary element. Too many supply chains, says Jan, focus on a lowest-cost approach with procurement as the primary driver.

She describes this as “lowest cost, at all cost” and says it results in all parties doing things for themselves cheaply as possible, minimising buffers, passing risk to others and leaving the whole chain more vulnerable.

“Planning should be the integrative glue that holds it together,” she says. “It should be the function that connects a supply chain. We see lots of exploitative procurement practices, expecting year-on-year cost downs, because procurement managers have been incentivized on margin.”

End-to-end supply chains?

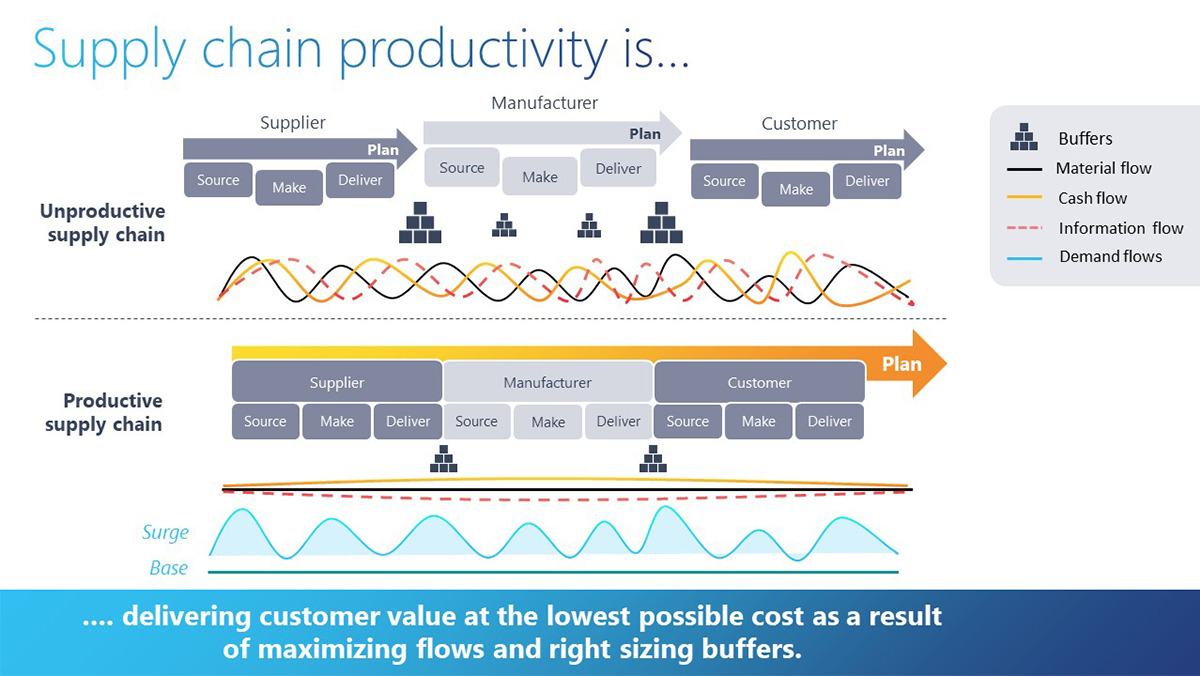

Jan’s ideal is to build what she calls “end-to-end supply chain optimisation” between retailers, manufacturers and suppliers. This creates flow and aims to manage the supply chain in a fairer way for everyone.

Buffers must be in the right place at the right amount. And there’s a collective responsibility for holding them and we don’t do things like promotions that mess up flow. The cheapest supply chain is one with steady demand, because it means minimal buffers, because you’ve got predictability.

And such end-to-end supply chains are likely to be less carbon intensive. “There is an inextricable link between productivity, sustainability and resilience,” says Jan. “The same principles underpin all three. If we could manage an end-to-end supply chain, so that we have flow and minimised buffers, within the current network configuration, it is likely to have the lowest carbon footprint, because you’ve got nothing in it you don’t need.”

Digitalisation is key

Like much else in modern organisations, supply chain optimisation requires technology. “We can’t do this without digitalisation,” says Jan, adding this is nothing new for manufacturing. “When I worked at ICI, we had electronic process control, it was just hard wired. Now the internet provides connectivity that spans the supply chain.”

Digitalisation enables us to understand demand and supply more accurately and we have the analytics platforms and the computing power to do the analysis we need in minutes.

This article was published by Lombard, read the original version here.