Dr. Marisa Smith (University of Strathclyde)

In 2021 Make UK1 outlined the need for manufacturing to attract skilled workers from all sections of society acknowledging the continuing challenges of the lack of diversity in the workforce. However, the current focus in manufacturing policy and practice on equality and diversity has been limited to gender and ethnic diversity. Although almost a quarter (23%) of the UK working age population are disabled2, the industry has lacked a real interest in the inclusion of disabled people.

The employment gap between disabled and non-disabled people has also remained consistently high at around 30% for the past 10 years, with a pay gap of almost 20% lower for disabled workers compared with non-disabled workers3. Moreover, in the UK, 32% of disabled people do not have basic digital skills4 and those with multiple disabilities are the most digitally disadvantaged. They often face barriers in basic access to the technology such as connection to Wi-Fi-network or finding and opening applications on their devices.

This inaccessibility of technology, together with rapidly growing digital capabilities, is exacerbating the digital divide between disabled and non-disabled people. There is also a strong business case to include more disabled people into work for innovation through diverse workforce. We know that diversity and inclusion have positive effect on firms’ productivity, innovativeness or quality5, so why has this been largely ignored by manufacturers?

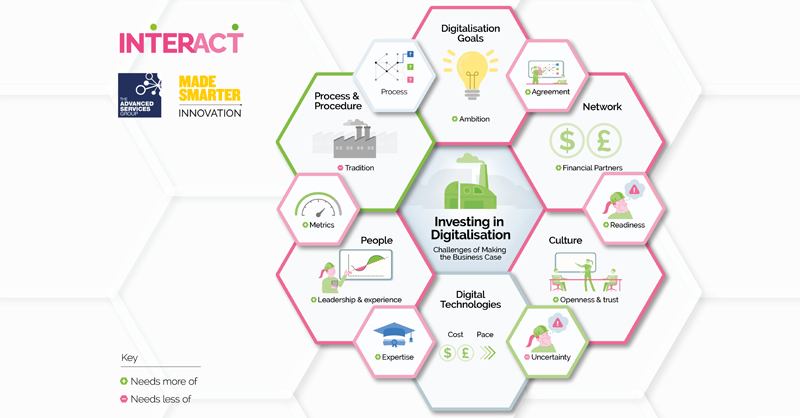

Recent research6,7 found that efforts to improve the suitability of industrial manufacturing workstations or the use of Industry 4.0 technologies for disabled people have still been superficial, favouring the inclusion of workers with milder disabilities and missing the complex interaction between the socio-technical aspects of inclusion. Our research explores how digital technologies, alongside an inclusive managerial mindset and accessible business practices, can create inclusive digitalisation in manufacturing.

Our project, ‘Manufacturing a Better Future – exploring disability inclusive digital manufacturing’, embodies the principles of socio-technical systems view where the benefits of the new technology are optimised alongside the humanisation of work, by looking into how the technological and social aspects interact and emerge together. This approach is closely in line with the social model of disability8. Based on this view, it is often the social barriers such as inaccessible physical environments, the attitudes (prejudice and discrimination) and the inflexibility of organisational procedures and practices that exclude disabled people from work, rather than medical conditions.

At the end of this project, we propose that we will have a greater understanding of how the digital inclusion divide, as well as the disability employment gap, can be narrowed through the inclusion of disabled people into the manufacturing ecosystem.

References

- Make UK (2021) UK manufacturing diversity & inclusion guide https://ktn-uk.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/KTN_Made-Smarter_UK-Manufacturing-Diversity-and-Inclusion-Guide.pdf?=MadeSmarterUK

- Scope (2022) https://www.scope.org.uk/media/disability-facts-figures/

- Together Trust (2023) https://www.togethertrust.org.uk/news/explaining-disability-employment-gap

- Lloyds (2021) Essential Digital Skills Report 2021, https://www.lloydsbank.com/assets/media/pdfs/banking_with_us/whats-happening/210923-lb-essential-digital-skills-2021-report.pdf

- Chaudhry, I. S., Paquibut, R. Y., & Tunio, M. N. (2021). Do workforce diversity, inclusion practices, & organizational characteristics contribute to organizational innovation? Evidence from the UAE. Cogent Business & Management, 8(1), 1947549.

- Teixeira, E. S., & Okimoto, M. L. L. (2018). Industrial Manufacturing Workstations Suitability for People with Disabilities: The Perception of Workers. In Advances in Ergonomics in Design: Proceedings of the AHFE 2017 International Conference on Ergonomics in Design, July 17− 21, 2017, The Westin Bonaventure Hotel, Los Angeles, California, USA 8 (pp. 488-497). Springer International Publishing.

- Mark, B. G., Hofmayer, S., Rauch, E., & Matt, D. T. (2019). Inclusion of workers with disabilities in production 4.0: Legal foundations in Europe and potentials through worker assistance systems. Sustainability, 11(21), 5978.

- Oliver, M. (2013). The social model of disability: Thirty years on. Disability & society, 28(7), 1024-1026.